In Parashat Bamidbar (last week’s reading) Moses and Aaron conduct a census of the Israelites. The tribe of Levi, who are placed in charge of managing the tabernacle (and later the Temple) under the supervision of Aaron’s family, are counted last. The tribe is subdivided into three clans according to Levi’s sons: Gershon, Kohath and Merari. What follows is a detailed account of each clan’s individual responsibilities.

The Torah first explains that the Kohathites were in charge of the most sacred objects in the tabernacle: the ark of the covenant, the table for the showbread, the golden menorah, the sacrificial altar and the service vessels for performing the sacrifices: fire pans, flesh hooks, scrapers, basins. After that, at the opening of this week’s parashah, Nasso, the focus switches to the Gershonite clan:

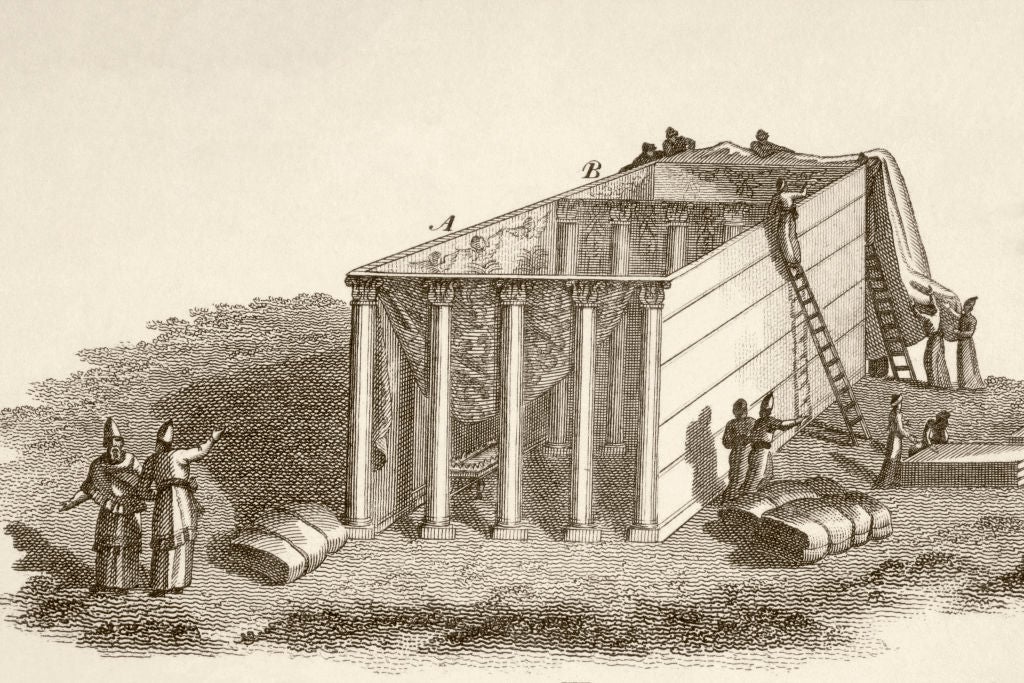

These are the duties of the Gershonite clans as to labor and porterage: they shall carry the cloths of the Tabernacle, the Tent of Meeting with its covering, the covering of dolphin skin that is on top of it, and the screen for the entrance of the Tent of Meeting …

(Numbers 4:24–26)

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

While the Kohathites are charged with managing the tabernacle’s most sacred objects, the Gershonites are charged with carrying its dressings: fabrics, curtains and coverings.

The Torah signals something unusual about the Gershonites through the levitical census structure. Gershon was Levi’s firstborn, yet God orders Moses to count the Kohathites first. (Numbers 4:1–2) They also receive the seemingly more vaunted assignment: handling the most sacred implements. This is an apparent violation of primogeniture, the idea that the firstborn is given special status.

Yet the text preserves Gershon’s dignity through subtle cues. The Gershonite census introduction employs the words gam hem (“they too”). Despite coming second in the census, they too deserve honorific census language. Of course, simply stating this raises a question: Are the Gershonites as esteemed as the Kohathites?

While the Kohathites carry ark, vessels and altar implements, the Gershonites handle the sanctuary’s outer shell: screens and curtains. This is essential, but in a less obvious way. A curtain is literally peripheral. And yet that becomes its defining characteristic, its qualification for a particular kind of sacred work.

Rather than simply carrying fabrics, the Gershonites maintain the permeable membrane between holy and ordinary. They occupy liminal space between inside and outside, sacred and profane, protection and exposure. They are guardians of this boundary precisely because they embody boundary-crossing, something encoded in their very name.

The name Gershon derives from Hebrew verbal root gimmel-resh-shin: “to drive out,” “to expel.” The same root is used for Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden (Genesis 3:24) and Hagar’s banishment from Abraham’s household (Genesis 21:10). The Gershonites are named for displacement that defines the human condition after paradise. They carry in their name the memory of exile, the experience of being pushed to the margins.

But here the paradox deepens: Exile becomes vocation rather than punishment. The root describing tragic expulsion becomes the foundation for sacred service. The capacity to create sacred space often emerges from experience of having lost it. Those who never lost sacred space may take it for granted. Those who must constantly reconstruct it approach each assembly with fresh eyes, renewed reverence.

The wordplay reveals further complexity. Ger also designates the “stranger who dwells among you” — the resident alien participating in Israel’s covenant while maintaining ethnic otherness. Gershonites are integrated into levitical service yet forever approaching work from an outsider perspective. This perpetual foreignness is not a liability but a theological asset. Their displacement-cum-vocation enables them to see what settled inhabitants miss.

The Gershonites embody the very act they perform. Their boundary-crossing work mirrors their boundary-crossing identity. They are what they do. They do what they are. This unity of identity and function finds its deepest expression in the nature of carrying itself.

Jewish law’s Sabbath carrying restrictions illuminate this connection. The Mishnah dwells heavily, even obsessively, on the laws of carrying items between public and private domains on Shabbat. It is also the first topic raised in the discussion of Shabbat: Before examining any other prohibited work, we must understand this fundamental act of boundary-crossing. The rabbinic insight: You may carry heavy furniture throughout your house but you may not carry a thread from doorway to street. Weight and distance matter less than domain-crossing — movement of objects across boundaries between private and public space. Carrying becomes “work” only when it transforms meaning through context-shifting.

The Gershonites perform this transformation as sacred vocation. Their literal carrying constitutes semantic porterage — transporting meaning from one domain to another. Each dismantling and reconstruction demonstrates new relationships between God (HaMakom, “The Place”) and specific places of Israel’s wilderness itinerary. In Gershonite hands, the portable sanctuary became a meditation on holiness itself, capable of transformation through movement.

Among objects entrusted to their care were the skin coverings, dolphin or seal hide forming the tabernacle’s outermost layer. These essential protective elements get overshadowed by theatrical rituals within the sanctuary. The coverings represent infrastructure rather than performance, protection rather than spectacle. The Gershonites are custodians of the overlooked essential. While the Kohathites handle liturgically visible elements — ark, altar, vessels — Gershonites tend hidden foundations that make sacred encounter possible. Their work enables moments of divine presence.

But their deepest teaching concerns the relationship between displacement and creativity. Their unique sacred work requires the stranger’s perspective. They remind us that the most essential sacred work may be performed by those appearing peripheral.

The Gershonites teach us that poetic and holy work involves moving a familiar burden to an unfamiliar place. And even when that burden seems slight or marginal, it makes all the difference.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on June 7, 2025. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.